For too long, planning has been blamed as the problem, not the solution. The government's response in continued deregulation of the planning regime to accelerate delivery not only misunderstands the problem but has failed to result in meaningful delivery. At worst, it has resulted in places of such poor quality they are damaging people’s life chances. The focus on housing numbers over quality placemaking has ignored the need for action on coordinated, infrastructure-led delivery.

The housing crisis is acute and multi-dimensional. Identifying effective solutions means being clear about the causes. The housing crisis is driven by two key factors: the collapse in investment in socially rented homes, and the government’s continued focus on planning consents and planning deregulation over practical delivery mechanisms. As a nation, we have ignored the fact that democratic planning and its ability to coordinate infrastructure, de-risk development, and set the right standards of design is the critical solution to housing the nation.

The increasingly permissive approach taken in England results in housing-led growth that often lacks key services or in no growth at all, where sporadic policy interventions, such as requirements for nutrient neutrality, delay development because of insufficient upfront consideration of sewage infrastructure.

It has been over 20 years since the government had a clear vision for homes and communities in England. There is an urgent need to lay the foundations of a long-term solution to these challenges, with a particular focus, through prioritising socially rented homes, on dealing with those most in housing need.

A key component of that vision relates to the delivery of new homes, underpinned by these core approaches:

- National strategic growth in the form of new settlements of at least 35,000 homes (80,000 people).

- Local strategic growth on a scale between 1,500 and 10,000 new homes in smaller new, renewed, and expanded communities.

- The contribution of the normal local plan process in meeting local needs.

Perhaps the most radical of these propositions is for a new generation of large, new settlements. The case for new settlements led by master developers, such as a Development Corporation, is powerful and would transform the sustainability, delivery rate, and long-term management of places. From the post-war New Towns programme to the eco-towns and Garden Communities, the past provides a wealth of lessons on how to build ambitious new communities while avoiding the creation of unsustainable places. Consistently, this highlights the important role of government in enabling and de-risking investment and delivery; the need for people to be properly involved in decision-making; and the need to ensure the long-term stewardship of the places we build.

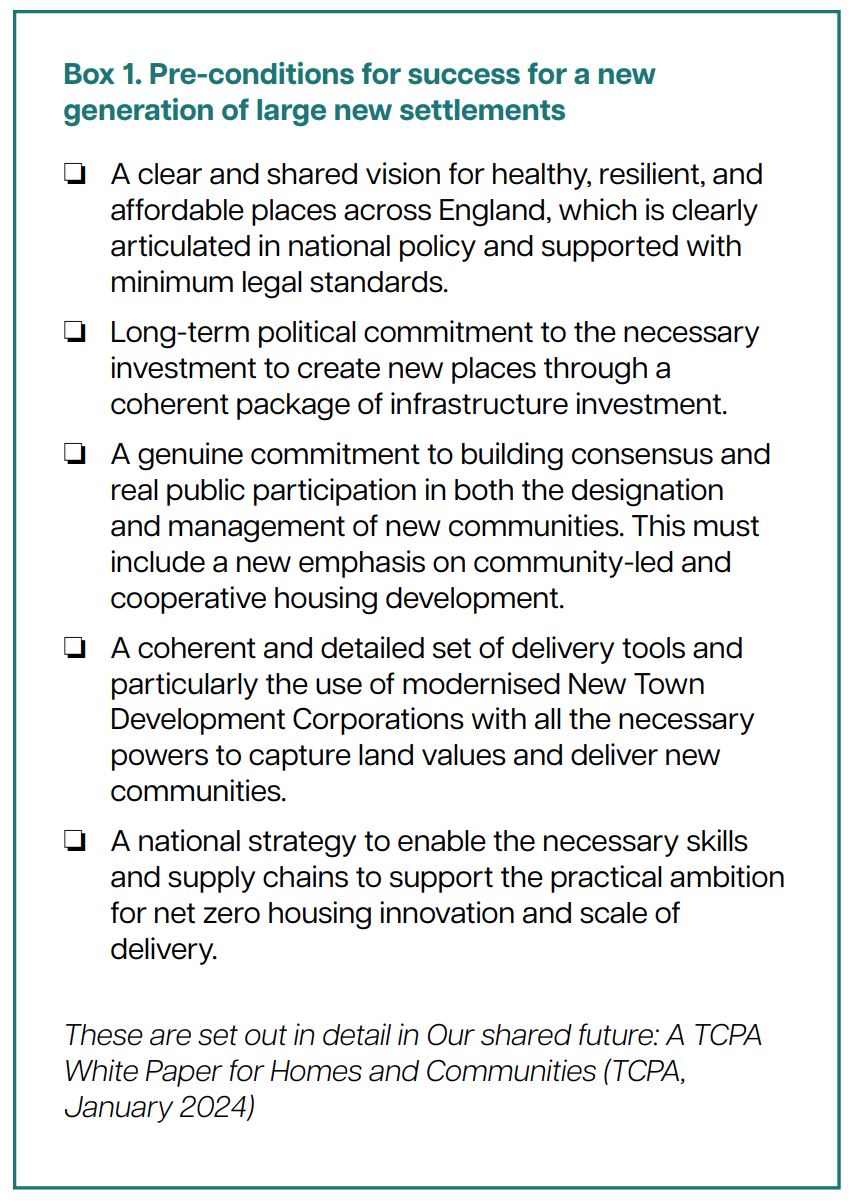

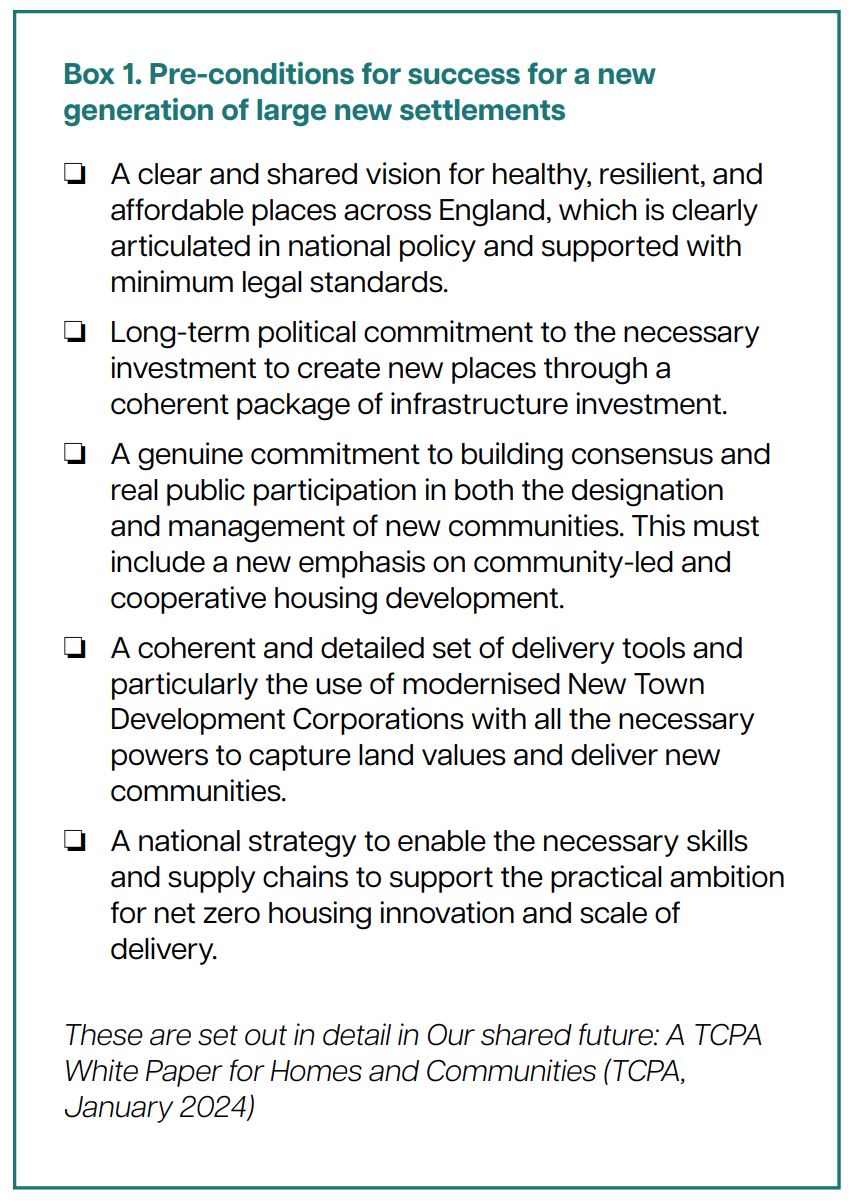

Learning these lessons means understanding the preconditions for the success of such a program of new settlements (see Box 1). These include those listed below and should be underpinned by a national strategic vision for homes and communities. A national spatial plan is essential to deliver this vision—to identify broad areas for development through an evidence-based process. Success requires the rebalance of political risk from the local to the national level, with government acting as an enabler to de-risk local public and private sector investment.

In exploring the solutions to the housing crisis, it is clear that the design principles and technical solutions necessary to deliver this vision already exist. The real challenge is whether we have the political will to implement them. Realising a vision of healthy, thriving places and solving the housing crisis requires a commitment to the highest design standards and the up-front, long-term patient investment to make it happen. Without a political commitment to invest, the housing crisis will go on damaging lives.